Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade opening credits

Contributed by Jayce Wheeled on Feb 18th, 2022. Artwork published in

.

Topics▼ |

Formats▼ |

Typefaces▼ |

10 Comments on “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade opening credits”

It’s actually more likely to be Eurostile Bold Extended 2, because the larger “UTAH 1912” title at around 00:03:40 has sharper inner joints on the A and 1 rather than the boxier inner joints as seen on Microgramma. It’s sometimes the only way to tell Microgramma and Eurostile apart in all-caps cases.

Further explaination here of differences: www.flickr.com/photos/stewf…

This would align the titling for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) more closely with the titling seen in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), which also used Eurostile, albeit in a slightly different style.

Further info on Raiders titles here: www.myfonts.com/WhatTheFont…

BONUS: The title sequence for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) uses Bauer Topic (aka Steile Futura) Bold, in an oblique setting not to be confused with the true italic.

See here: www.myfonts.com/WhatTheFont…

And, as mentioned in my previously linked WhatTheFont post about the Raiders title sequence, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) used Columna Open instead of Open Capitals Roman (aka Open Kapitalen).

Thanks, Patrick. As you say, all-caps Eurostile Extended is virtually identical to Microgramma Extended. You are correct that there’s a tiny difference in the design of the crotches, but this refers to the original metal versions. The joints were more open as Microgramma was designed for tiny sizes (hence the name). I’m not sure how much this distinction holds up for later adaptations. Of the myriad phototype versions, there were probably some with sharper inner joints that were nevertheless labeled Microgramma. Now is such a version in fact Eurostile in disguise? #ExistentialTypeQuestions

The more obvious distinction used to be that Microgramma was caps only, while Eurostile had a lowercase. That has been blurred, too: The digital Microgrammas by URW, Linotype, and Elsner+Flake all include a lowercase. They do feature the boxier inner joints, though.

Yes, they are very easily mixed up—particularly in all-caps at smaller sizes or slightly blurry film titles which can effectively hide the differences. The additional digital lowercases will probably continue the confusion. I’m sure it is possible some type vendors may have mislabelled Microgramma Bold Extended as Eurostile Bold Extended. I know Letraset dry transfer sheets did sometimes list both names at the top, as in “Microgramma (Eurostile),” as though they were one and the same. And I’ve by no means seen every available version but all of the pre-digital Microgramma Bold Extended listings/samples I have seen (be they metal, phototype or dry transfer) usually retain those specific boxier joints (ink traps?) on the AMNVW, 1 and 4, even at sizes of 72pt and above. Because of this, the angled flag/stroke on the 1 is also different, appearing less steep in Eurostile Bold Extended and falling more sharply in Microgramma Bold Extended. This is also noticeable in the “UTAH 1912” title, making it more likely to be typeset in some version of Eurostile Bold Extended. Given the degraded clarity of the titles, that’s as specific as I can be.

As for how to answer whether a Eurostile dressed as a Microgramma is still a Eurostile, the prevalance of renamed clones with very minor changes in the age of phototype and beyond has made it almost impossible to identify every version and its various distinctions. Oftentimes, the distinctions are so slight between listings as to be indistinguishable or otherwise irrelevant. I’m content to just identify the original typeface name with a decent showing of all the available glyphs, an available digital version (if possible) and then list other known aliases or similar typefaces if relevant. So, if a Eurostile had been, unbeknownst to me, mislabelled or issued under the name Microgramma, I would simply identify it as a Eurostile, because visually it still is. Tracking down the exact variation, its alias and its source, in that kind of a scenario, is not something I would value as necessarily essential. I’m much more interested in the unknown or unidentified typefaces – particularly those of the phototype era as so many of those seem to have been lost to time.

The W in particular, along with many other characters, are also quite a bit wider in Microgramma Bold Extended compared to Eurostile Bold Extended. See above enlargement with type comparison from the opening titles (00:01:35) of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989).

I delved a bit deeper into the Microgramma/Eurostile issues. Aside from the ink traps on the AMNVW, 1 and 4, the differences in pre-digital versions are much less pronounced than I first thought. Width differences I highlighted seem to be a result of sampling innaccurate specimens based on digital versions of Microgramma that are much wider than they should be. The only noticeable width difference in the pre-digital releases lies in the 0 (zero), which is less wide in Microgramma Bold Extended. The other differences still apply, however, with the angled strokes of the AMNVW, 1, 4 and 7 being steeper in Microgramma Bold Extended.

In looking for samples I stumbled across some strange listings. Are we certain on Eurostile for 1962 release? Are we certain Microgramma didn’t have a lowercase added post-release?

This showing from Type Faces | Volume One by Graphic Arts Typographers, Inc., lists Microgramma Extended Upper and Lower Case as well as Microgramma Bold Extended Upper and Lower Case. The two samples look very Eurostile in appearance to me, as if they have been typeset in Eurostile but referred to as Microgramma, but the small sample size makes it hard to tell definitively. However, this is from October, 1961, a bit before Eurostile is generally reported to have been released.

archive.org/details/sim_art…

Reports from January, 1958, state that typefaces designed and manufactured by Società Nebiolo are to be distributed to American printers and graphic artists by Amsterdam Continental Types and Graphic Equipment, Inc. The first of the Nebiolo typefaces to be offered is Microgramma.

My thinking is that maybe the successful 1958 release of Microgramma in America prompted some type suppliers to list or market the upcoming 1961/2 arrival of the very similar Eurostile faces under the established Microgramma name. If Microgramma never had lowercase, then this is the only reasonable explanation I can reach. This might be the origin of the interchangeable Microgramma/Eurostile naming that resulted in later anomalies and confusion.

Thank you for digging deeper, and for sharing your finds here, Patrick.

When referring to “pre-digital versions”, I think it’s important to differentiate between metal and photo type. The former comes in various sizes which might exhibit size-specific differences, in terms of proportions, spacing, etc. They can be subtle or drastic, see e.g. ATF Othello. (I haven’t compared different sizes of Microgramma.)

The 1962 date is given by all the usual sources. Here’s a Nebiolo specimen from Letterform Archive’s collection. It describes Eurostile as “new series inspired by Microgramma” and has a “7–62” note on the back, which I believe stands for the printing date, July 1962. A Microgramma specimen from 1959 (“12–59”) doesn’t show a lowercase. Later specimens that include both typeface families show Microgramma as all-caps design and Eurostile with lowercase. Eurostile was announced in the U.S. in January 1963.

Cutting and casting a full family of foundry type with several styles and numerous sizes could easily stretch over more than one or two years, making release dates a moving target. The showing with lowercase labeled “Microgramma” from October 1961 is very likely Eurostile. I can imagine that it’s an advance showing of the very first styles and sizes. Maybe Nebiolo themselves meant to stick to the established name initially, and only came up with a distinct name for the extension in the following months.

Thanks for the info.

I was not aware a metal type took quite so long to produce. That’s some wait time from the initial US announcement of Eurostile to release! Simpler times, I suppose.

I previously mentioned the “0” (zero) being wider in Eurostile nero largo (bold extended). This isn’t the case with either the Società Nebiolo or Amsterdam Continental Types metal releases. Must have just been another innacurate showing. I suspect the author possibly recycled the “O” in place of the “0” (zero) when putting it together. Apologies for the misinformation.

In terms of the original Nebiolo releases of Microgramma / Eurostile Bold Extended, this image, sourced directly from Nebiolo samples, should more sufficiently illustrate the subtle differences I was attempting to explain above.

In smaller point sizes, with sufficient ink bleed or as the result of some other type of of blurring, these subtle differences can become almost invisible. And, if Eurostile Bold Extended is typeset in all-caps, it can look nearly identical to the caps-only Microgramma Bold Extended. In such cases, these subtle differences are the only way to spot the difference.

Thanks a lot, Patrick! That’s a handy visualization.

As for the production time of a metal typeface family: it depends on many factors, of course. A bigger foundry that focused on one typeface could complete even a bigger series much faster, of course. It was fairly common to launch with a few key styles in the most sought-after sizes first. And if that met a demand, additional sizes, weights, and widths followed later. After all, it was a huge investment. One can find mentions in specimens and typeface ads saying “larger sizes in preparation”, or “the Extrabold is currently being cut”.

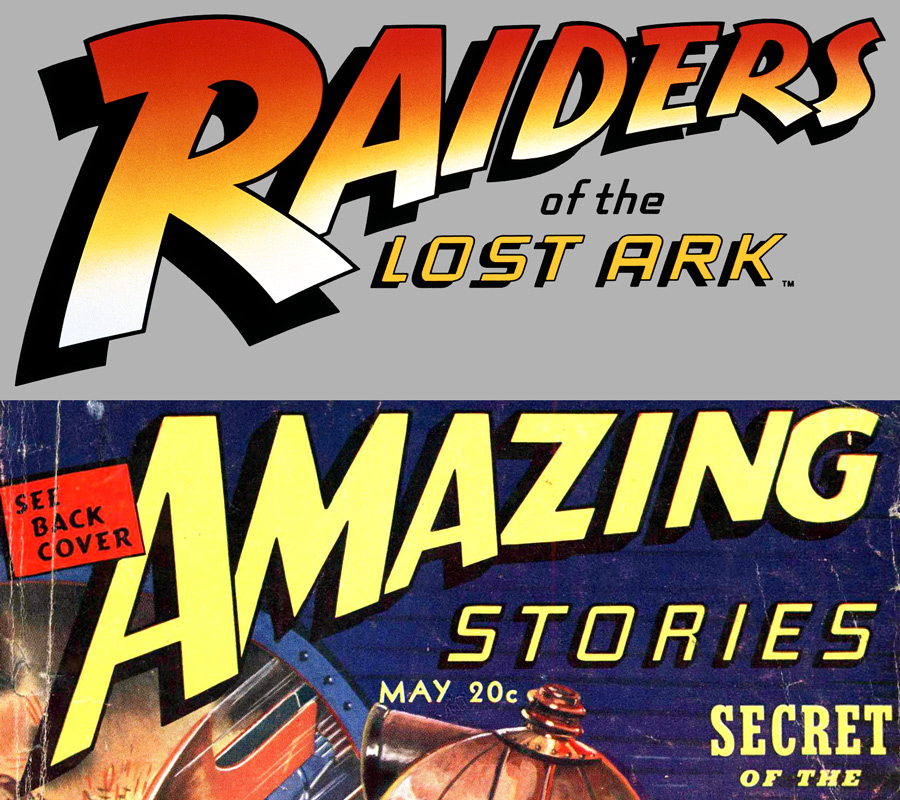

On a somewhat related note, the “Raiders of the Lost Ark” and subsequent Indiana Jones film series logos are highly reminiscent in both layout and style to the cover lettering of long running American science fiction magazine Amazing Stories, as seen on issues published between June, 1938 to March, 1953. Steven Spielberg would also later develop the anthology television series Amazing Stories, which was released in 1985.