The Story of Our Friend, the Fat Face

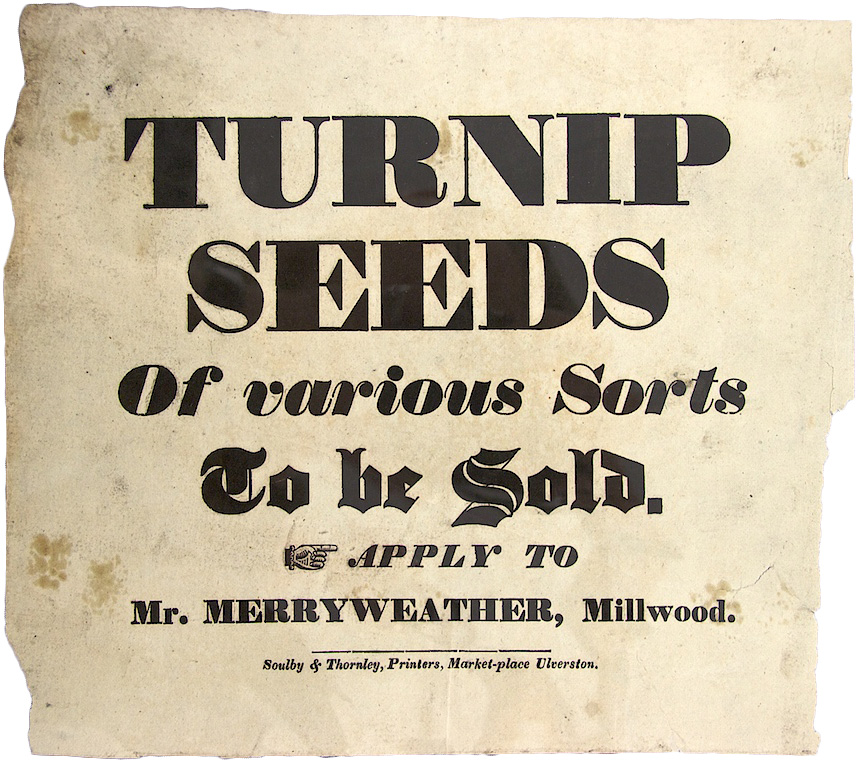

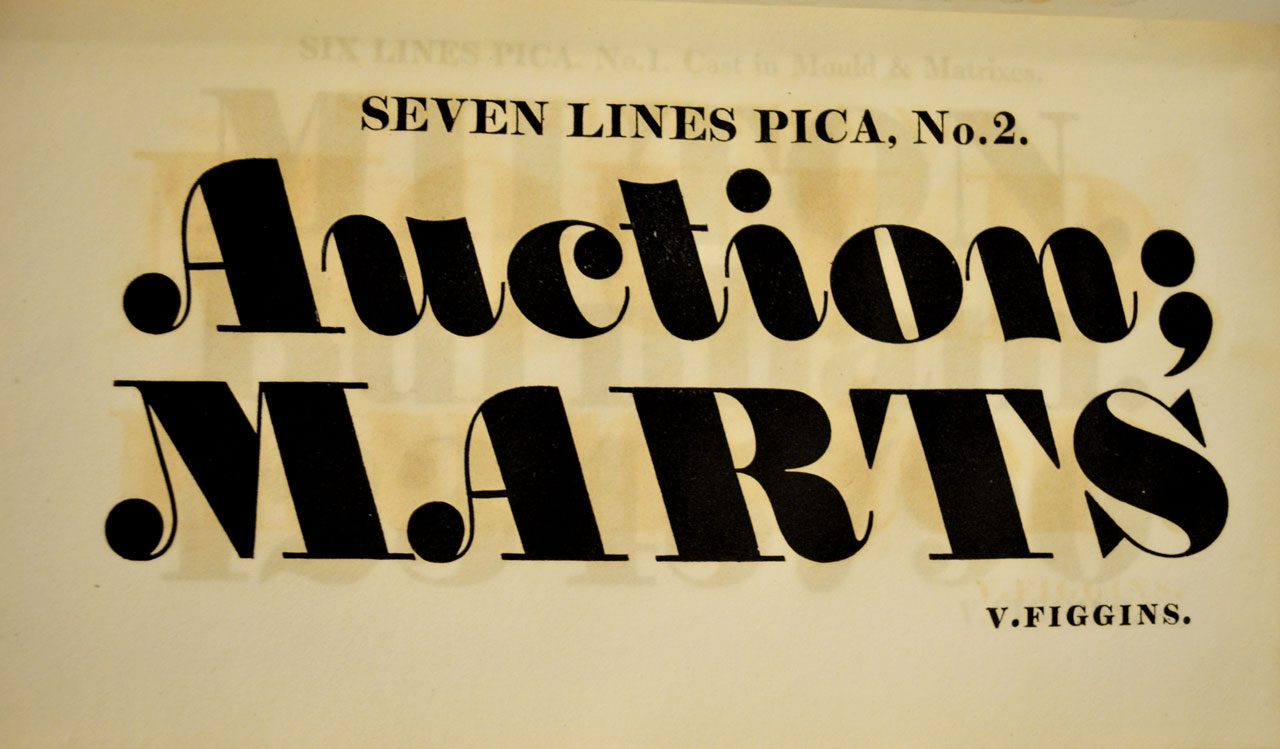

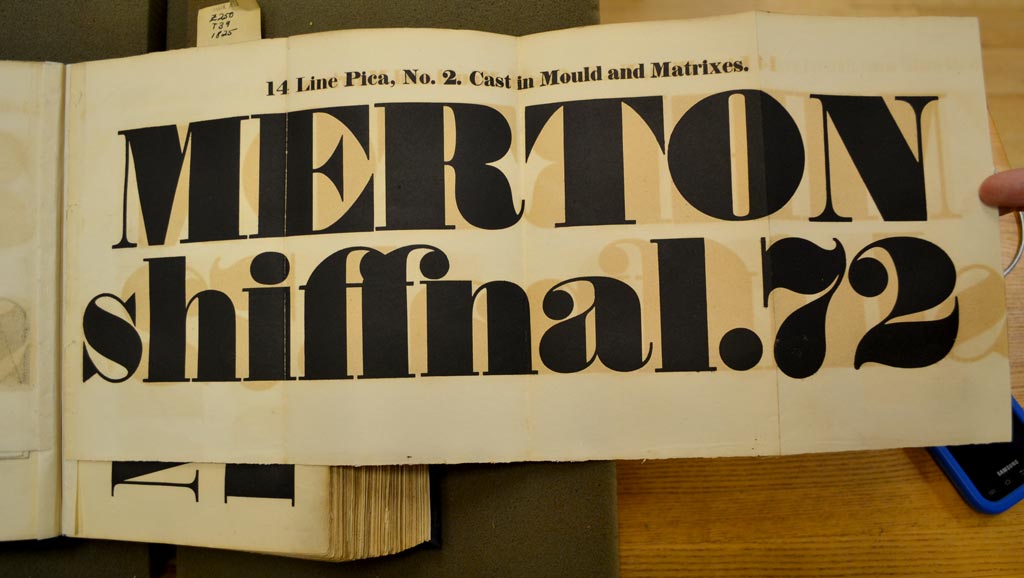

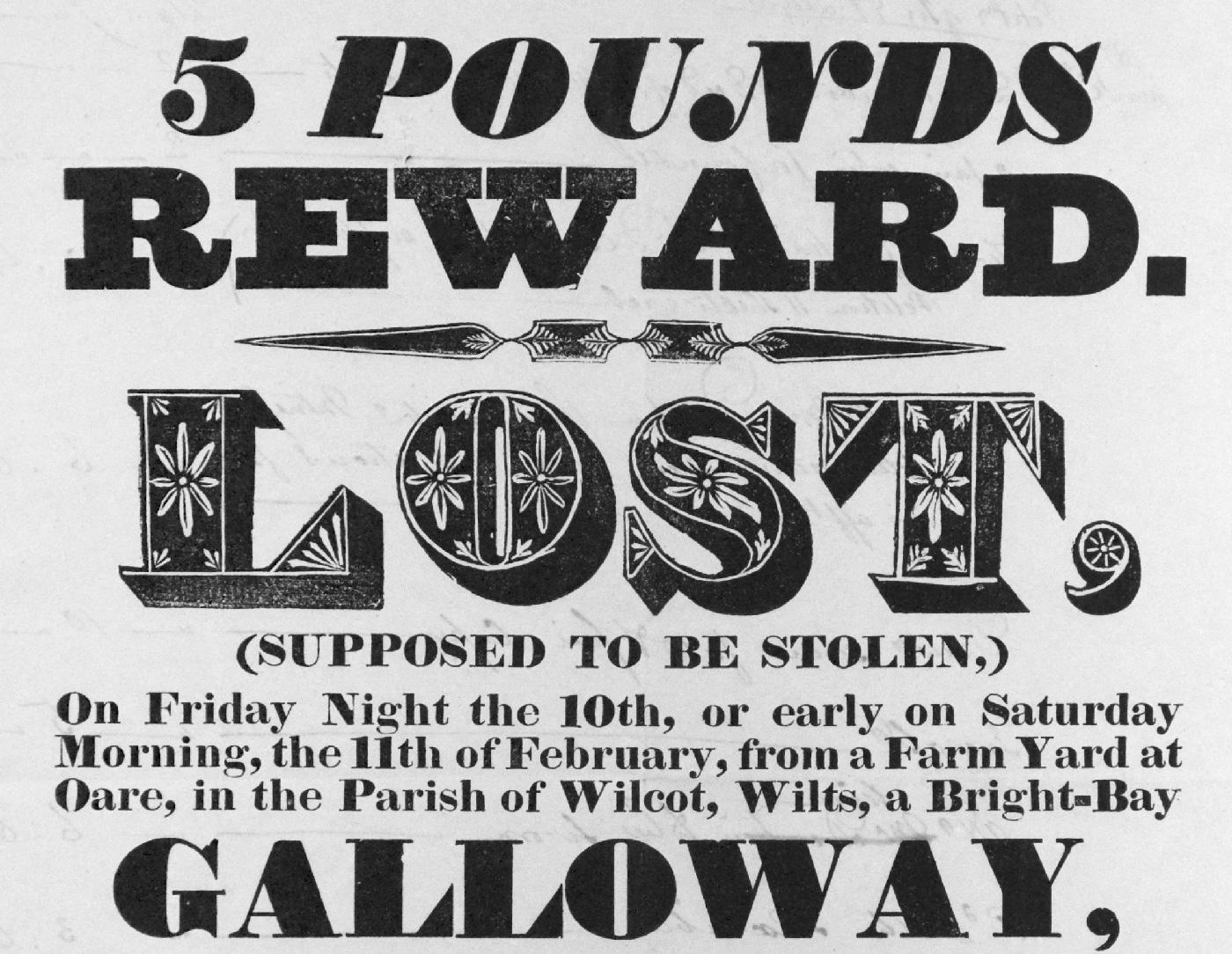

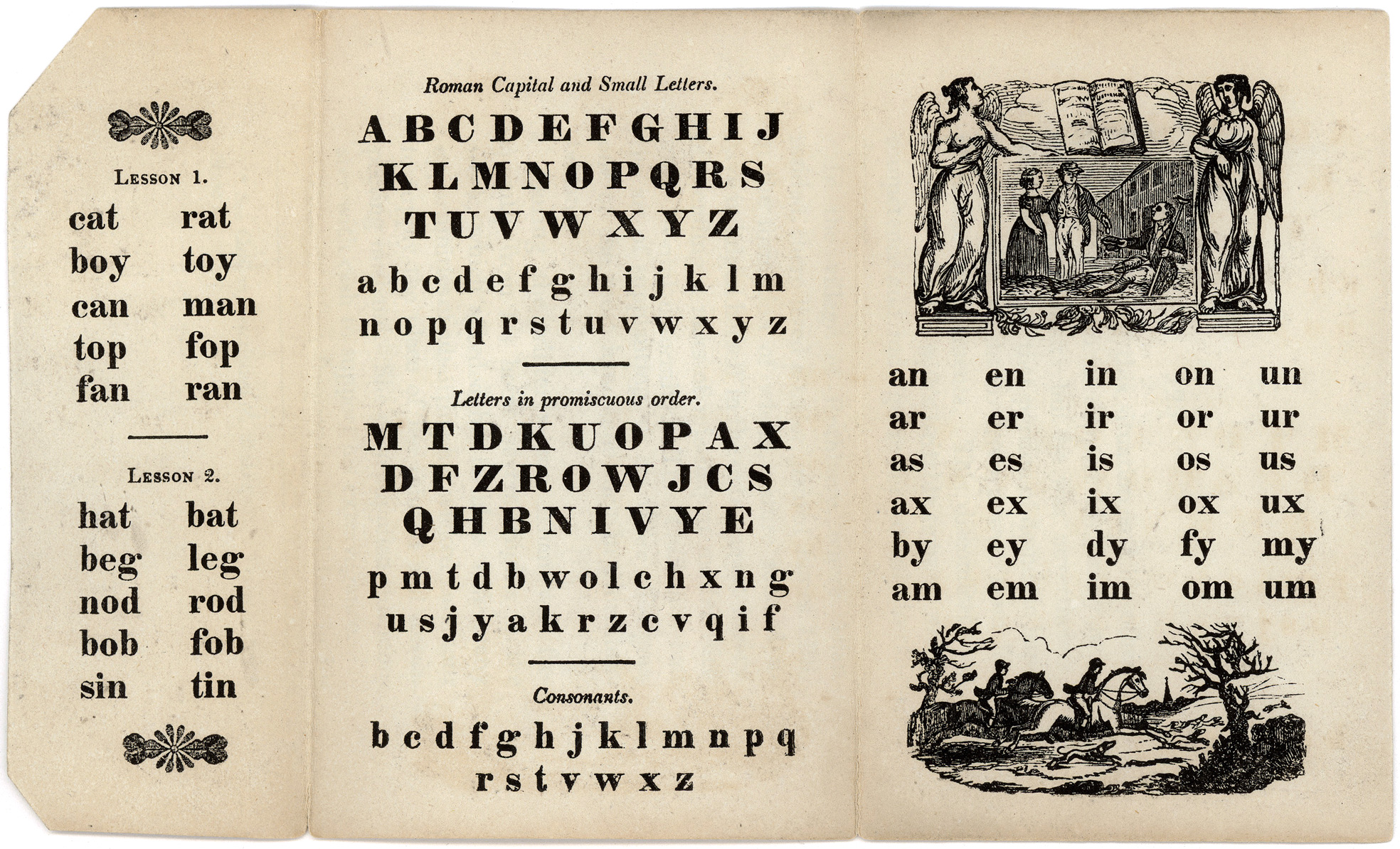

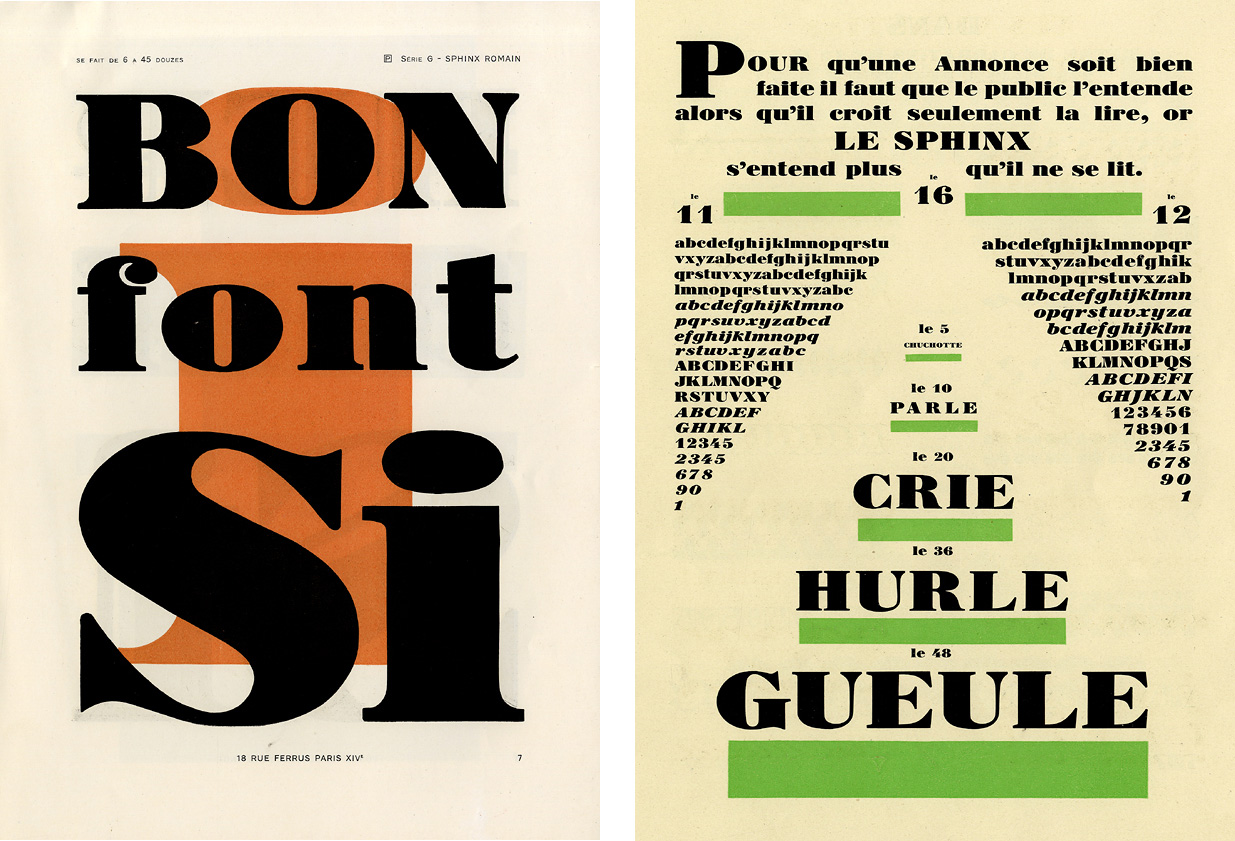

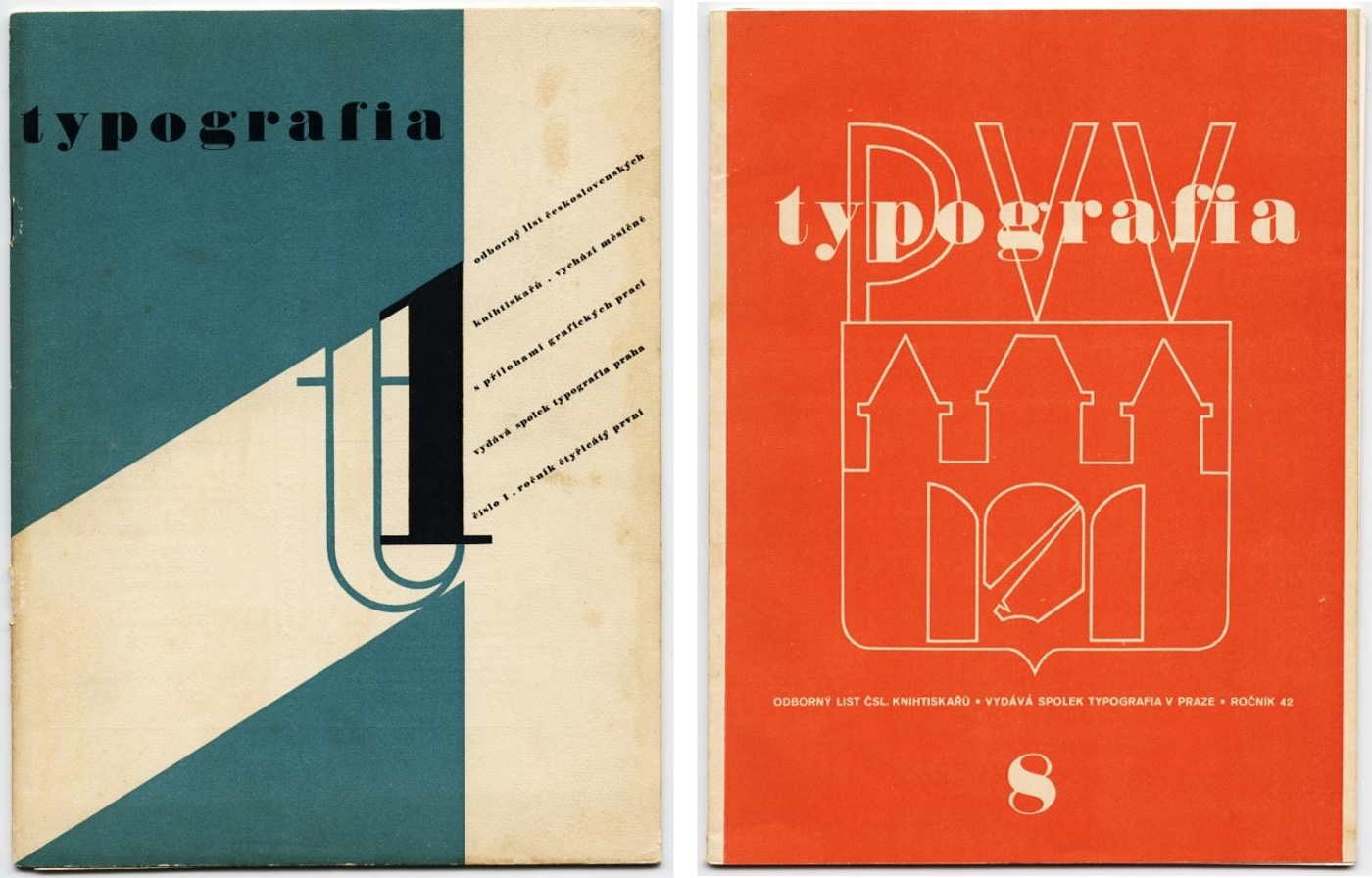

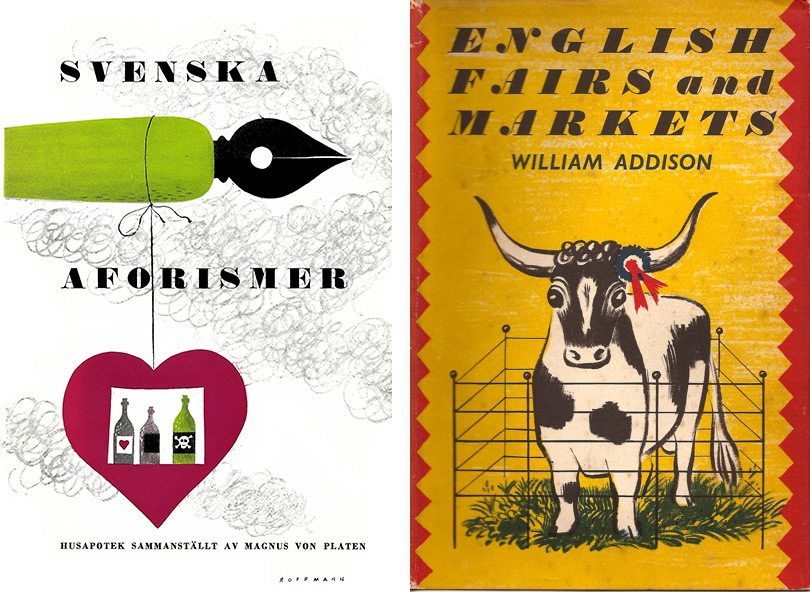

Journey back to a time when serifs were Antique, sans serifs were Grotesque, and extra bold faces were Fat.

Contributed by Jennifer Kennard on Feb 6th, 2014. Artwork published in

circa 1826

.

13 Comments on “The Story of Our Friend, the Fat Face”

Great collection of images and information. Thanks for posting.

It’s clever to use the phrase “minding [or learning] his 'P’s and 'Q’s” here, recognizing that the cliche comes from type composition. But as long as we’re doing that knowingly, I’d propose using lowercase forms of the letters in that phrase, since those are the ones that need to be kept straight!

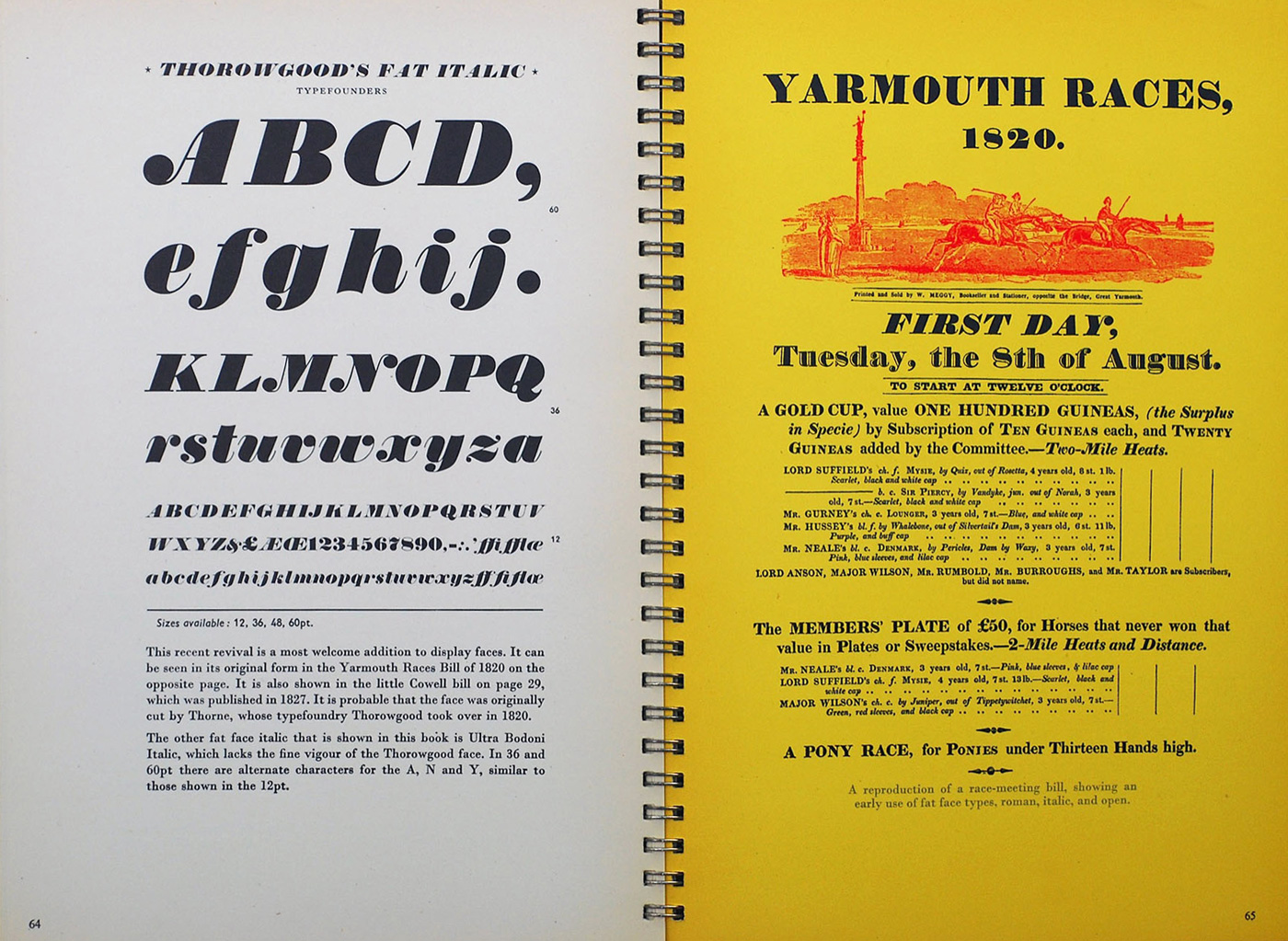

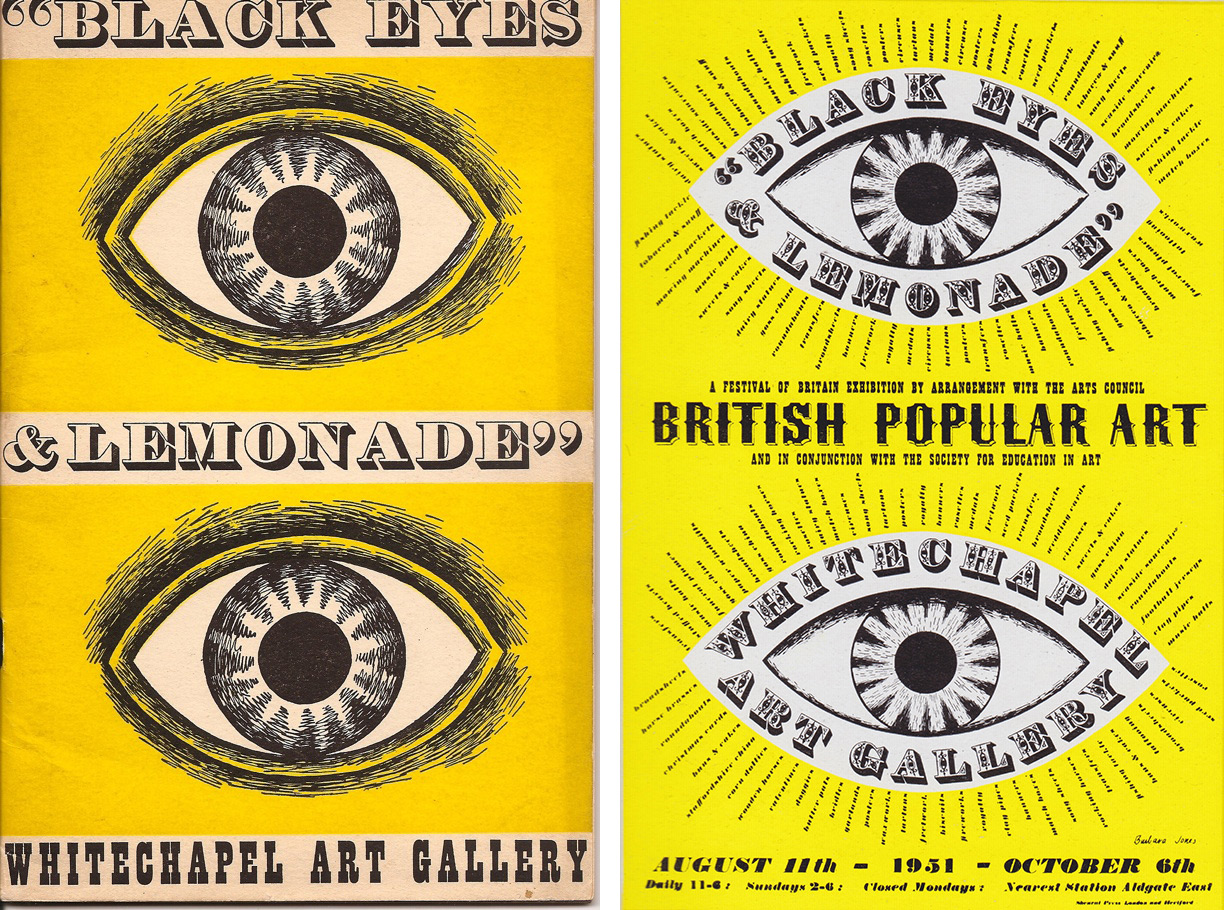

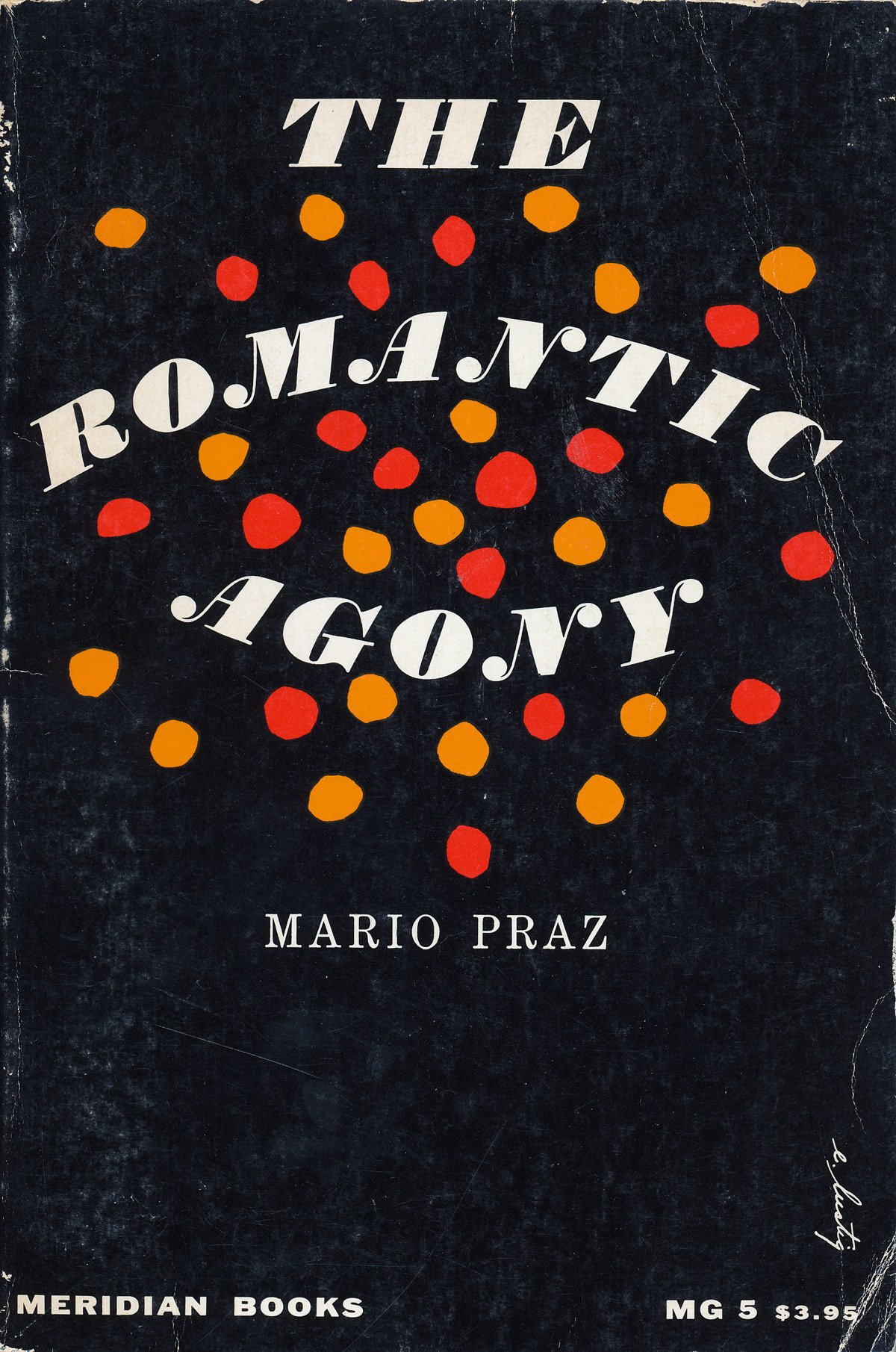

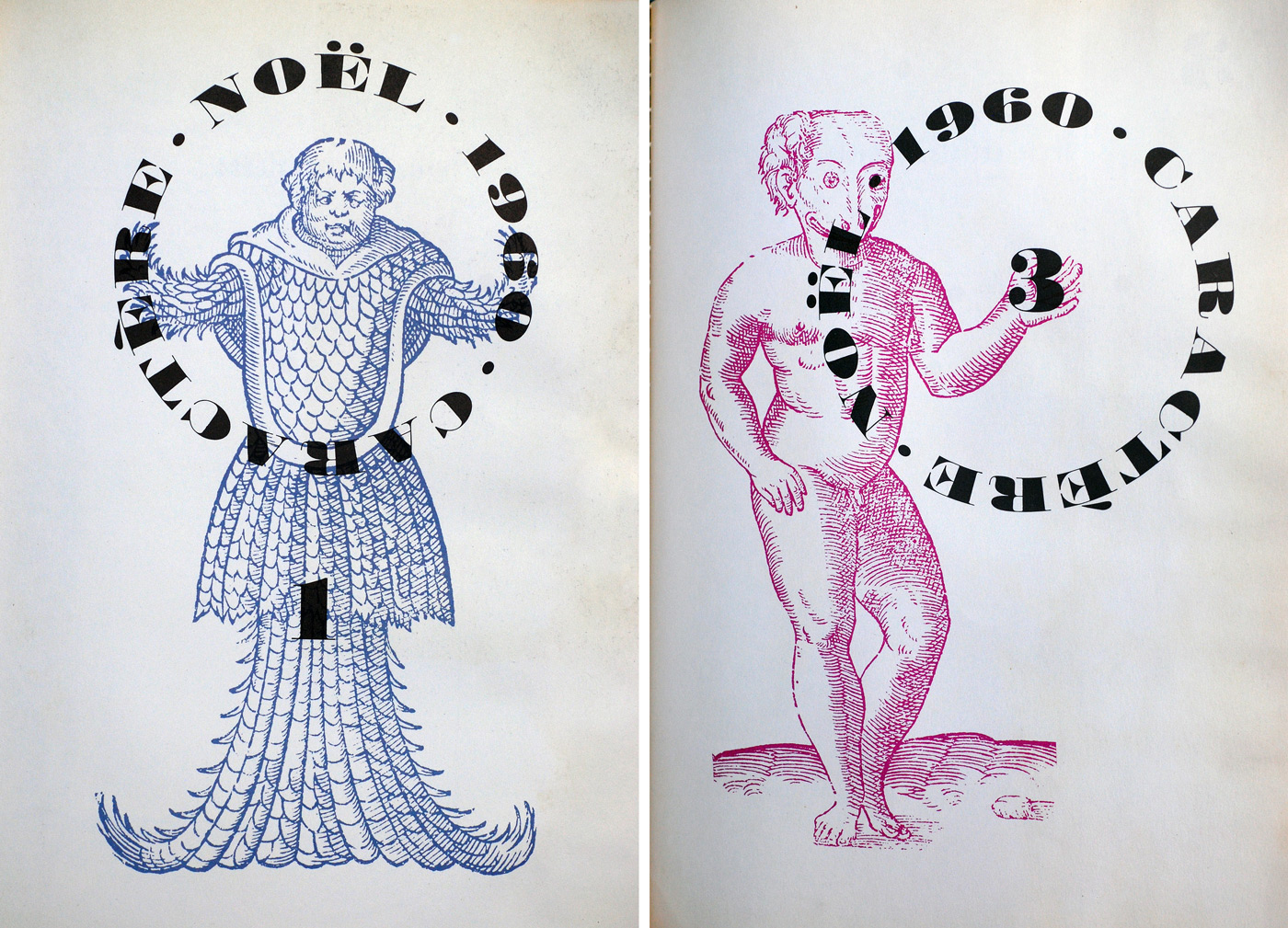

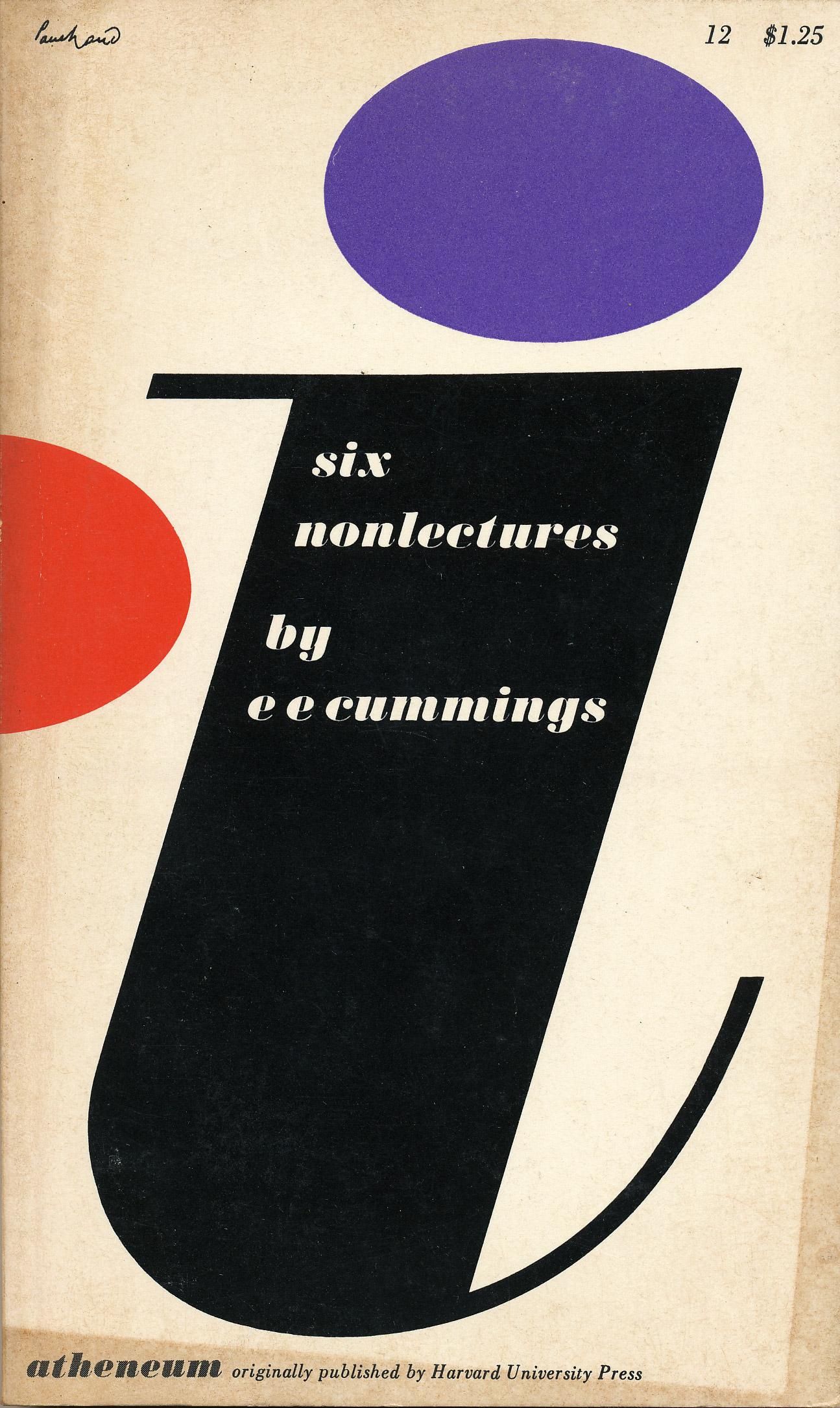

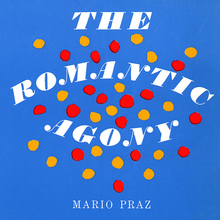

Those huge ball terminals always strike me as simultaneously the most exciting and the most frustrating part of italic fatface usage. They can really screw up intraword spacing (The word POUNDS in the lost horse poster being a good example). So I really love the ROMANTIC AGONY cover, in which Elaine Lustig Cohen turns the would-be-distracting dots into a design feature of the whole composition. Ingenious!

Right you are about the ‘p’s and ‘q’s, Craig. Fixed.

The Monofil logo, according to the credits in “Marken und Signete” was designed by the Atelier Dorland, (based in Düsseldorf/Berlin). But no individual credit given, other than the agency. Might be by A.E. Wuttke, he did a few lettered pieces for the Dorlan agency, but that could be a long shot.

Just stumbled on another mid-19th-century fat face, this one from Boston Type Foundry in their 1860 catalog:

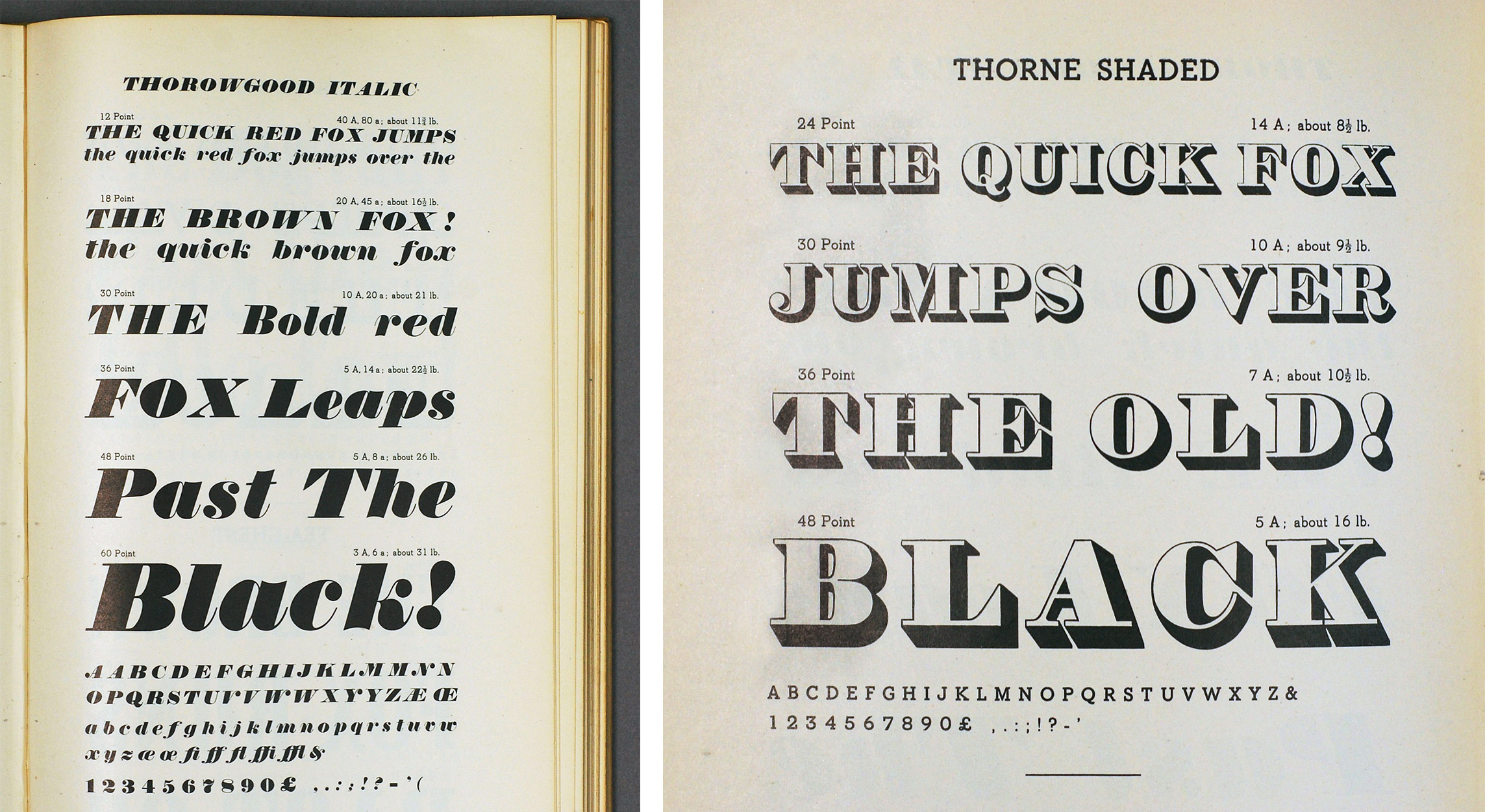

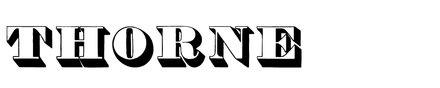

Also from that specimen book, this “Italic Shade” with swashes which reminds me (for varying reasons) of Thorne Shaded, Ingeborg Block, and ITC Magnifico.

And another page (65) from the Boston specimen where the design was called “Full-Face”.

Elephant by Carter and Cones is a lovely fat face that would fit on your list.

Thanks, Ian! The elephant in the room, so to say. Despite the fact that it came bundled with various Microsoft products, Elephant can easily be overlooked: It is available only from a few select sources, and it has been updated under a different name: Big Figgins.

How can you overlook Madrone from the Adobe Wood Type collection? It is truly elephantine!

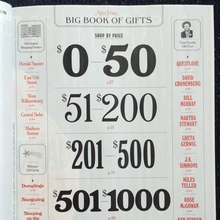

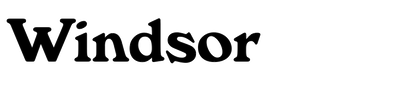

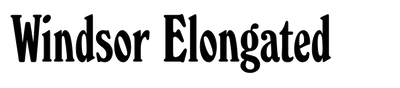

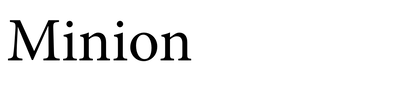

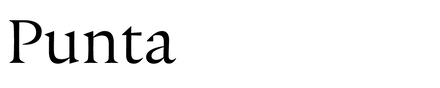

Images under “Revivals, Reinterpretations, and Progressions” are not displayed.

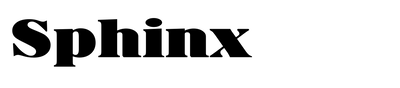

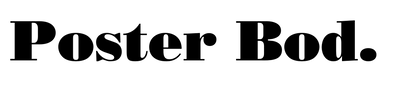

Thanks, Arnaud! We will look into this. The images show one-line samples of the typefaces mentioned in this section.

Edit: The images are back up.

Just updated the main article to mention that Bruce’s fat face was issued as early as 1828. Here’s the largest size shown in that catalog:

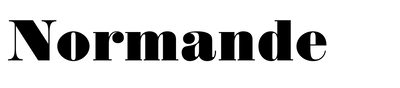

It looks like the new movie “booksmart” is using Normande for its title, all in lower case. Some of the supplemental materials seem to have been done in Thorowgood (such as this GIF and the Spanish version of the movie poster). The telltale difference, to this amateur’s eye at least, is the lowercase “r,” which connects to the ball in different locations in the two fonts.